There’s no question that these past eighteen months have seen a gratifyingly powerful turnaround in our nation’s affairs. Yes, we still have a way to go to undo the damage done by the Obamunists. Yes, there remain problems of significance whose solutions are anything but obvious. All the same, the economic resurgence, the destruction of ISIS, the improvement in America’s international standing, and Americans’ generally more optimistic outlook are all things to celebrate.

Still, we mustn’t blind ourselves.

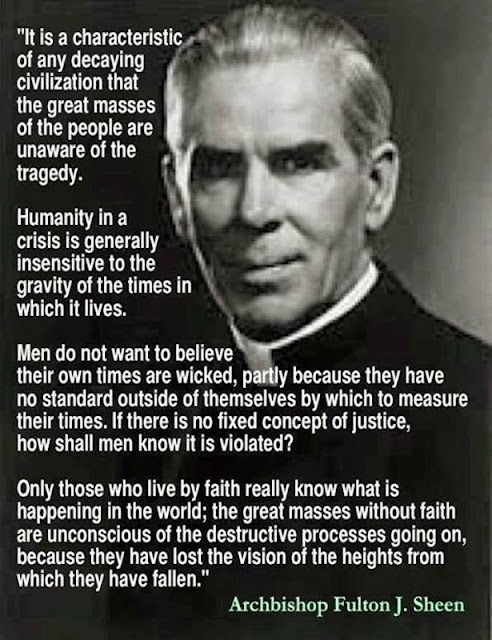

A few days ago I stumbled across the following:

Archbishop Fulton Sheen was one of the Twentieth Century’s great religious thinkers and apologists. His writings remain immensely popular and influential among English-speaking Catholics. Yet many younger Catholics – and a distressing number of older ones – have never become acquainted with his work. So I pasted that image into an email and sent it to a great many friends and Web acquaintances, with the subject line “A Voice From The Grave?” and added a line beneath the image:

Bishop Sheen wasn’t speaking to us specifically...was he?

Here are some of the replies I received:

- True enough.

- He might as well be.

- [T]hat could explain the complete obliviousness to the violation of the Golden Rule most people are demonstrating.

- [T]he millennials have been duped into self-gratifying stupidity. Including my kids, even after homeschooling to protect them.

“Men do not want to believe their own times are wicked.” Of course we don’t. If “our times” are wicked, that makes the odds rather strong that we ourselves are wicked, or at least have passively tolerated the advance of wickedness among and around us. Who wants to believe that of himself, however judgmental he may be about those around him?

But how is one to know whether his times are wicked? Only by recourse, as Archbishop Sheen has told us, to “a fixed concept of justice.” In an age of moral relativism, where is such a concept to be found – and how are we to know whether it truly expresses justice?

Glad you asked!

An alarming number of voices are stridently rejecting – even denouncing – faith. Some are individually well known. Others promulgate their faithlessness through organizations such as the Freedom From Religion Foundation. And of course there are the militant atheists of the Web, who seem to pop up and go on the attack wherever and whenever others discuss religious matters. It should tell us something that most members of that latter group go by anonymizing monikers.

Because most persons are sufficiently confrontation-averse to back away from noisy, angry evangelists, those noisy types often seem to get their way without much resistance. We who challenge them to demonstrate why their faith – and it is a faith just as much as is Christianity; don’t let them tell you different – is superior to ours often receive scornful, ad hominem replies. Most common are “You must be weak to need faith,” and “You have to be stupid to believe that crap.” (I shall leave my habitual reaction to such insults to my Gentle Readers’ imagination.)

The crowning irony of such exchanges is that the militant atheist routinely awards himself the palm of superior intelligence specifically because he’s an atheist. Yet what is he doing? In the usual case, he reaps nothing but resentment plus a resolution to exclude him from future conversations. Seldom does he even try to offer a rational case for his position – and isn’t enhanced rationality supposed to go along with high intelligence?

Yet they are many, though perhaps fewer than they’d like us to believe, and far less intelligent than they’d like to believe of themselves.

Our contemporary plagues of cruelty, injustice of all sorts, indifference to the lot of one’s neighbor, and the embrace of self-limiting and self-destructive behavior are all founded on the rejection of a single, all-important axiom:

Reality, as the saying goes, is that which is indifferent to your opinions. Bishop George Berkeley advanced the opposite thesis: that what we call reality is really only the artifact of our perceptions. Samuel Johnson snorted the notion aside nearly three centuries ago and provided a simple demonstration of its falsity. Yet the notion has persisted in some men’s minds ever since.

The descent from Berkelian subjective idealism to outright solipsism is quick and easy. But the solipsist is left without a mooring or a star to steer by. His entire world collapses upon himself, his sensations, and his opinions.

In a world where nothing is real except oneself, no concept of justice, fixed or otherwise, can ever be formulated.

Pilate therefore went into the hall again, and called Jesus, and said to him: Art thou the king of the Jews?

Jesus answered: Sayest thou this thing of thyself, or have others told it thee of me?

Pilate answered: Am I a Jew? Thy own nation, and the chief priests, have delivered thee up to me: what hast thou done?

Jesus answered: My kingdom is not of this world. If my kingdom were of this world, my servants would certainly strive that I should not be delivered to the Jews: but now my kingdom is not from hence.

Pilate therefore said to him: Art thou a king then? Jesus answered: Thou sayest that I am a king. For this was I born, and for this came I into the world; that I should give testimony to the truth. Every one that is of the truth, heareth my voice.

Pilate saith to him: What is truth?[John 18:33-38]

Yet we struggle with the concept of objective reality. The reasons are several. For me, the crux came with my introduction to quantum physics. Others have different crises. The problem, however, is common.

Reality is complex. However determinedly we strain to know it in all its aspects, we are forever constrained by the limitations built into our human nature. Our perceptions have limits. Our technology has limits. Even our minds have limits. In consequence, what we can know has limits, and always will. The great adventure of science is an attempt to push those limits outward. Yet however far we may extend them, they will always exist.

What is will always be wider than what we know.

We invest so much respect and confidence in the sciences because they provide us knowledge. They exist to advance what we know...at least, they try to do so. But the region within human knowledge is finite. The region beyond it is infinite and always will be.

What the sciences ultimately do for us was captured by a great writer in one of his very best stories:

At last reports, [the count] had been involved in some highly esoteric tampering with the Haertel equations—that description of the space-time continuum which, by swallowing up the Lorentz-Fitzgerald contraction exactly as Einstein had swallowed Newton (that is, alive), had made interstellar flight possible. Ruiz-Sanchez did not understand a word of it, but, he reflected with amusement, it was doubtless perfectly simple once you understood it.

Almost all knowledge, after all, fell into that category. It was either perfectly simple once you understood it, or it fell apart into fiction. As a Jesuit—even here, fifty light-years from Rome—Ruiz-Sanchez knew something about knowledge that Lucien le Comte des Bois-d’Averoigne had forgotten, and that Cleaver would never learn: that all knowledge goes through both stages: the annunciation out of noise into fact, and the disintegration back into noise again. The process involved was the making of increasingly finer distinctions. The outcome was an endless series of theoretical catastrophes.

The residuum was faith.[James Blish, A Case of Conscience]

Science’s search for knowledge, despite its fits and starts, produces results upon which we can rely within the limits that currently obtain. The reliability of those results gives rise to the researcher’s rule that any new theory that purports to explain what has lain beyond our understanding up to now must also explain what we believed we already understood – and at least as well as the theory it proposes to displace. If it cannot do so, it cannot be a true advance.

The reliability of what we know, within the limits that currently obtain, is reason enough to have faith in the objectivity of reality – even if we can never know it to its ultimate extent.

The remarkable recent movie The Case For Christ dramatizes protagonist Lee Strobel’s investigation into whether Christianity has a basis in fact. This investigative journalist came away convinced:

- That Jesus of Nazareth existed;

- That He was crucified and died on His cross;

- That on the third day thereafter, He rose from the dead.

That is the irreducible core of Christian faith. If it really happened, it confirms as well as any series of events possibly could that Jesus of Nazareth was what He said He was: the Son of God, possessing full divine authority to pronounce the New Covenant under which Mankind could win salvation and eternal bliss in Heaven. If it didn’t happen, Christianity is, in the words of a secondary character, “a house of cards.”

Now, the evidence that Strobel amassed convinced him. It might not convince others. There’s always room to dispute the evidence of historical events that one did not witness personally. But even to argue over the evidence is to accept the axiom that there is an objective reality. If there is, and if we can amass reliable knowledge about it, then it has laws. Those laws will express an objective standard upon which we can rely.

Throughout human history, the standard that has conduced to human happiness and flourishing has been constant:

- Intergenerational respect and loyalty; (“Honor thy father and thy mother;”)

- Respect for the sanctity of human life; (“Thou shalt not murder;”)

- Respect for fidelity to solemn promises; (“Thou shalt not commit adultery;”)

- Respect for private property and its owner; (“Thou shalt not steal;”)

- Respect for fidelity to truth in testimony; (“Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor;”)

- Avoidance of envy-powered cupidity; (“Thou shalt not covet;”)

- Respect for the bonds implied by community. (“Love thy neighbor as thyself”)

That standard, in other words, works reliably: a compelling demonstration of the reality beneath it. It is a standard by which justice may be known and injustice may be detected. And it is exactly the standard that Jesus proclaimed throughout His ministry in first-century Judea.

Archbishop Sheen knew whereof he spoke. He’d made it the center of his life. I don’t doubt that he wept to see so many reject it as fantasy for the “weak” and “stupid.” But equally so, he saw what flowed from that rejection. We, have we but the will, can see it too.

Have we the will to act on what we see?

May God bless and keep you all.

1 comment:

Unfortunately, the Roman Catholic Church no longer provides the standards by which our age can be judged. It, too, has been swallowed by the Age. Perhaps truth is hiding among the Eastern Orthodox.

Post a Comment